.jpg) |

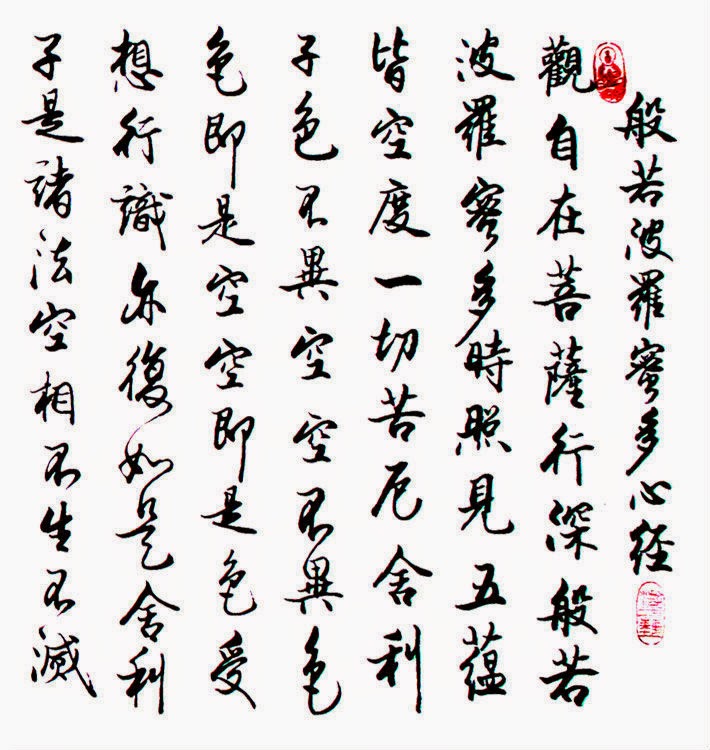

| a gandharva serenades Brahmā |

We have one quite thorough study of the gandharva by Oliver Hector de Alwis Wijesekere (1945). However Wijesekere indulges in a level of speculation, involving multiple shifting interpretations of the meanings of names and creative reading of myth, that is hardly acceptable by modern standards of scholarship. His is an imaginative reading, no doubt, but his exposition seems to be an attempt to create a mythology rather than describe one. His account is frequently tendentious, arguing towards the fixed goal that the Vedic texts explain the Pali references when they do not! For example he claims;

A subsequent study by Cuevas (1996: 279-281) is a useful start, but is far from comprehensive. It also suffers from a certain amount of speculation as to how to interpret Ṛgveda (RV) passages. Some of Cuevas's references to RV simply do not tally with the content he attributes to them.

So we must proceed with caution and with due attention to primary sources.

Etymology

"...it is seen that most of the above discussed mythological associations of the Vedic notion of Gandharva are found [in the Pali Nikāyas] but in a more developed form..." (86)This claim is not simply false, it is an outrageous over-statement that is completely at odds even with his own baroque reading of the Vedas. And yet it is typical of the tone of the whole article. The article is still useful for identifying relevant passages, but these all require careful and sober reconsideration in light of contemporary methods and studies of Vedic myth.

A subsequent study by Cuevas (1996: 279-281) is a useful start, but is far from comprehensive. It also suffers from a certain amount of speculation as to how to interpret Ṛgveda (RV) passages. Some of Cuevas's references to RV simply do not tally with the content he attributes to them.

So we must proceed with caution and with due attention to primary sources.

Etymology

It's not entirely clear what the name gandharva means. Georges Dumézil (1948) suggests an Indo-European ancestor *Guhondh-erwo- though he does not give a meaning for this root. Modern sources on Indo-European language do not list a root *Guhondh. He also links it via the Latin februo 'purify' to *Guhedh-rwo. There is a root *gwhedh in AHD, which means 'to ask, to pray' (bid is a rare cognate). However the dictionaries say that the origin of februo is uncertain, possibly related to 'fume' from PIE *dheu-.

Vasubandhu repeats a folk etymology of gandharva as gandhaṃ arvati 'it eats smells'. However modern dictionaries do not list 'eat' as a meaning of √arv. Monier-Williams, for example, lists this as a fanciful root meaning 'hurt, kill'; while Apte just has 'kill'. The name is various translated into Buddhist Chinese as 食香 (eater of odours), 尋香行 (one who goes in search of odours), 香陰 (fragrant secret?), 香神 (fragrant spirit), 尋香 (searching for odours), 樂天 (music god, heavenly musician), etc; and transliterated as 乾闥婆 (Middle Chinese gandalpa, Pinyin gāntàpó). (Digital Dictionary of Buddhism). The character 香 can mean 'smell, odour, fragrance, incense, etc.'. This suggests that the name was widely interpreted according to folk etymology.

Most Buddhist sources try to derive the name from gandha 'smell'. Sanskrit gandha is usually said to be from √ghrā 'to smell' and ghrāṇa 'nose' (i.e. the smeller) from a PIE root *gu̯hrē- (PED sv gandha); possibly related to English fragrant though other sources derive this from PIE *bhrə-g-. Cognate words from *gu̯hrē- are few and include Greek osphrainomai (ὀσφραίνομαι) 'to catch scent of, smell'; and Tocharian kor/krāṃ 'nose'.

Edward Washburn Hopkins (1968) says the Viṣṇu Purāṇa (1.5.44) derives the name from gam-dhara'song maker' from √gā/√gai'to sing' and √dhṛ'to bear'. Unfortunately the Viṣṇu Purāṇa doesn't say this and the citation is to a different verse; and in any case dhara means 'bearer', not 'maker'. By contrast the translation by Wilson (1840: 41) has:

This is not to say that gaṃ-dhara is a stupid idea for an etymology of gandharva, because it isn't. If gaṃ comes from √gā 'to sing' and dhar- from √dhṛ'to bear' (with guṇa of the root vowel) and we form an adjective by adding the primary suffix -va we get to our goal without mangling the language. In practice the nasal in gaṃ- would change to gan when followed by dharva because of sandhi rules. In support of this derivation we can site primary derivative forms from √dhṛ such as dharuṇa, dhartṛ, dhartra and dharman (with suffixes -uṇa, -tṛ, -tra, -man). Against this idea is the fact that dharva is not a standalone word, or found in any other context in Sanskrit dictionaries.

Gaṃ-dharva seems no less plausible than deriving gandha from √ghrā, in fact it seems more plausible, in the sense there are fewer anomalous changes to explain: √gā must lighten its root vowel; √ghrā on the other hand must lose aspiration, lose the liquid /r/, and lighten its root vowel, not to mention that -dha is not a standard suffix and would have to be derived from some other root such as √dhā. In terms of derivatives, √ghrā has forms ghrātṛ, ghrāṇa (suggesting that it doesn't undergo the kinds of changes being suggested by gandha).

In this case gandharva would mean 'a bearer of songs', which certainly fits the role assigned to them in the late Vedic and Epic literature.

Vasubandhu repeats a folk etymology of gandharva as gandhaṃ arvati 'it eats smells'. However modern dictionaries do not list 'eat' as a meaning of √arv. Monier-Williams, for example, lists this as a fanciful root meaning 'hurt, kill'; while Apte just has 'kill'. The name is various translated into Buddhist Chinese as 食香 (eater of odours), 尋香行 (one who goes in search of odours), 香陰 (fragrant secret?), 香神 (fragrant spirit), 尋香 (searching for odours), 樂天 (music god, heavenly musician), etc; and transliterated as 乾闥婆 (Middle Chinese gandalpa, Pinyin gāntàpó). (Digital Dictionary of Buddhism). The character 香 can mean 'smell, odour, fragrance, incense, etc.'. This suggests that the name was widely interpreted according to folk etymology.

Most Buddhist sources try to derive the name from gandha 'smell'. Sanskrit gandha is usually said to be from √ghrā 'to smell' and ghrāṇa 'nose' (i.e. the smeller) from a PIE root *gu̯hrē- (PED sv gandha); possibly related to English fragrant though other sources derive this from PIE *bhrə-g-. Cognate words from *gu̯hrē- are few and include Greek osphrainomai (ὀσφραίνομαι) 'to catch scent of, smell'; and Tocharian kor/krāṃ 'nose'.

Edward Washburn Hopkins (1968) says the Viṣṇu Purāṇa (1.5.44) derives the name from gam-dhara'song maker' from √gā/√gai'to sing' and √dhṛ'to bear'. Unfortunately the Viṣṇu Purāṇa doesn't say this and the citation is to a different verse; and in any case dhara means 'bearer', not 'maker'. By contrast the translation by Wilson (1840: 41) has:

"The Gandharbas [sic] were next born, imbibing melody: drinking of the goddess of speech, they were born, and thence their appellation."This corresponds to VPu 1,5.46:

dhyāyato 'ṅgāt samutpannā gandharvās tasya tatkṣaṇāt |Which I understand to say:

pibanto jajñire vācaṃ gandharvās tena te dvija ||VPu 1,5.46 ||

The gandharvas have arisen at the same moment as his contemplation,So not 'song-maker', or even 'song-bearer'; nor 'imbiber of melody', but in fact 'drinking speech' (pibanto vācam), i.e. imbibing speech at birth, noting that Vāc is the name of speech personified.

Born drinking Speech, those gandharvas are therefore twice born.

This is not to say that gaṃ-dhara is a stupid idea for an etymology of gandharva, because it isn't. If gaṃ comes from √gā 'to sing' and dhar- from √dhṛ'to bear' (with guṇa of the root vowel) and we form an adjective by adding the primary suffix -va we get to our goal without mangling the language. In practice the nasal in gaṃ- would change to gan when followed by dharva because of sandhi rules. In support of this derivation we can site primary derivative forms from √dhṛ such as dharuṇa, dhartṛ, dhartra and dharman (with suffixes -uṇa, -tṛ, -tra, -man). Against this idea is the fact that dharva is not a standalone word, or found in any other context in Sanskrit dictionaries.

Gaṃ-dharva seems no less plausible than deriving gandha from √ghrā, in fact it seems more plausible, in the sense there are fewer anomalous changes to explain: √gā must lighten its root vowel; √ghrā on the other hand must lose aspiration, lose the liquid /r/, and lighten its root vowel, not to mention that -dha is not a standard suffix and would have to be derived from some other root such as √dhā. In terms of derivatives, √ghrā has forms ghrātṛ, ghrāṇa (suggesting that it doesn't undergo the kinds of changes being suggested by gandha).

In this case gandharva would mean 'a bearer of songs', which certainly fits the role assigned to them in the late Vedic and Epic literature.

Gandharva in the Ṛgveda

The name gandharva occurs just 20 times in the Ṛgveda (1028 hymns in about 10,000 verses).

Roughly speaking, books 2-7 are considered the earliest layers, 1, 8 & 9 are middling, and book 10 latest. Thus the idea of gandharva appears to have some antiquity, but is of very minor interest to the early composers of RV. Gradually it became slightly more important, but was never central. The various mentions tap into different aspects of the gandharva (some of which seem incompatible). In citing RV I'll use the translations of Doniger (1981) as a reference point. Where the Sanskrit is clear enough I'll provide my own rendering, but RV is frequently obscure and beyond my linguistic level.

- book 1 - 2 references

- book 3 - 1 reference

- book 9 - 4 references

- book 8 - 2 references

- book 10 - 11 references

Roughly speaking, books 2-7 are considered the earliest layers, 1, 8 & 9 are middling, and book 10 latest. Thus the idea of gandharva appears to have some antiquity, but is of very minor interest to the early composers of RV. Gradually it became slightly more important, but was never central. The various mentions tap into different aspects of the gandharva (some of which seem incompatible). In citing RV I'll use the translations of Doniger (1981) as a reference point. Where the Sanskrit is clear enough I'll provide my own rendering, but RV is frequently obscure and beyond my linguistic level.

One of the tricky aspects of trying to essay this subject is that the sources are vague. So for example Cuevas (280) says that, "The Brāhmaṇic sources recount how Soma remained with the gandharvas, and how the gandharva Vivāsvat (the Vedic father of Yama and Yamī) had stolen the vital juice." However in most stories it is either Indra riding on an eagle who steals Soma (RV 4.36) or an eagle who steals Soma and gives it to Indra (RV 4.18). Elsewhere Vivāsvat is certainly said to be the father of the twins Yama and Yamī (RV 10.17; 10.10). And elsewhere e.g. RV 10.10.4(cd) where Yama's twin sister, Yamī, is trying unsuccessfully to seduce him, Yama says:

gandharvó apsú ápiyā ca yóṣāsā́

no nā́bhiḥ paramáṃ jāmí tán nau

The gandharva and the maiden in the waters,

Is our supreme origin, that is our relationship.

If we follow the implication then Vivāsvat was a gandharva. On the other hand Doniger (1981: 250 n.8) comments that gandharva here is "Probably the sun, born of the waters, but perhaps just any gandharva." In fact Vivāsvat is usually a name for the sun.

Cuevas also cites RV 10.85 several times: the sūkta about the marriage of Sūryā (daughter of the sun). This sūkta also mentions Viśvāvasu and a gandharva plays a role. Doniger calls Viśvāvasu "a Gandharva who possesses girls before their marriage" (273 n.21 - commenting on 10.85.21). The associated verses (21-22) are an exorcism of Viśvāvasu. The marriage ritual seems to conceive of the bride Sūryā being married four times: to Soma, a gandharva, Agni, and a human, though it's not clear what the significance of this is. Doniger mentions that this is a template for marriage, and thus the ritual may conceive of all women going through this process of being married first to the gods and then her husband proper. At any rate the text is concerned to send the gandharva packing as an unwanted intrusion. We'll see that gandharvas sometimes possess people in the Upaniṣads as well.

In the mid-Vedic period text, Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (ŚB 3.2.4), we find another completely different myth of the stealing of Soma that is tied up with the character of Viśvāvasu. The Brāhmaṇas are commentaries on the ritual of the Vedas and date from the period after the composition of the Vedas and well before Buddhism (ca. 1000-800 BCE). In this story it is Gāyatrī who steals Soma, but afterwards she was carried off by the gandharva Visvāvasu (the names are close but different). The devas thinking "the gandharvas like women" sent Vāc to them and she returned with Soma. However the gandharvas proposed that the devas marry Soma while they married Vāc. And at this point we get the moral of the story. Gandharvas seriously recited the Vedas to Soma, while the devas frivolously sing and dance to attract Vāc. And this is why, according to ŚB, women are attracted to frivolous things, since they follow Vāc rather than Soma. (cf Eggelington). Commentators use this passage to characterise gandharvas generally as interested in women and all things sexual, though in fact the text tried to characterise them as serious and pious.

What both Wijesekere and Cuevas do is take all the stories as being of the same period and the same weight, as though a story from ŚB can be taken without any reservation or caveats as from the same body of literature as a story from RV. However, historically the Brāhmaṇa texts represent a very different phase of Vedic culture, many centuries removed, and while there are obvious relations, we must be very cautious about simply equating all Vedic literature. Unpicking the resulting mess from these studies is laborious and time consuming. Almost as much as doing it from scratch. And if the scholarly literature is confused in this way, then we can see why the popular literature is confused. And given the importance of the gandharva to understanding the Buddhist afterlife, this is salutary.

To carry on with our survey of the Ṛgvedicgandharva, we may say that the relationship of the sun and the waters is a little counter-intuitive, but in at least some Vedic cosmogonic myth the first substance to emerge from the primordial chaos is water, and from water all things are created, including the sun. Soma is said to combine fire and water and thus bestow immortality (RV 4.18, 4.26; Doniger 1981: 128). It is worth noting the similarities with the so-called twin-miracle (yamaka-pātihāriya) in which the Buddha expresses fire and water from his body while hovering in the sky.

One of the important observations on the Vedic gandharva is that it lives (or they live) in the antarīkṣa or interim realm, the liminal space between earth (pṛthivī) and heaven (svarga). They are also associated with Soma in various ways. We saw that some stories attribute the theft of Soma to gandharvas, but they are also seen to empower Soma, eg RV 9.113.3

Cuevas also cites RV 10.85 several times: the sūkta about the marriage of Sūryā (daughter of the sun). This sūkta also mentions Viśvāvasu and a gandharva plays a role. Doniger calls Viśvāvasu "a Gandharva who possesses girls before their marriage" (273 n.21 - commenting on 10.85.21). The associated verses (21-22) are an exorcism of Viśvāvasu. The marriage ritual seems to conceive of the bride Sūryā being married four times: to Soma, a gandharva, Agni, and a human, though it's not clear what the significance of this is. Doniger mentions that this is a template for marriage, and thus the ritual may conceive of all women going through this process of being married first to the gods and then her husband proper. At any rate the text is concerned to send the gandharva packing as an unwanted intrusion. We'll see that gandharvas sometimes possess people in the Upaniṣads as well.

In the mid-Vedic period text, Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (ŚB 3.2.4), we find another completely different myth of the stealing of Soma that is tied up with the character of Viśvāvasu. The Brāhmaṇas are commentaries on the ritual of the Vedas and date from the period after the composition of the Vedas and well before Buddhism (ca. 1000-800 BCE). In this story it is Gāyatrī who steals Soma, but afterwards she was carried off by the gandharva Visvāvasu (the names are close but different). The devas thinking "the gandharvas like women" sent Vāc to them and she returned with Soma. However the gandharvas proposed that the devas marry Soma while they married Vāc. And at this point we get the moral of the story. Gandharvas seriously recited the Vedas to Soma, while the devas frivolously sing and dance to attract Vāc. And this is why, according to ŚB, women are attracted to frivolous things, since they follow Vāc rather than Soma. (cf Eggelington). Commentators use this passage to characterise gandharvas generally as interested in women and all things sexual, though in fact the text tried to characterise them as serious and pious.

What both Wijesekere and Cuevas do is take all the stories as being of the same period and the same weight, as though a story from ŚB can be taken without any reservation or caveats as from the same body of literature as a story from RV. However, historically the Brāhmaṇa texts represent a very different phase of Vedic culture, many centuries removed, and while there are obvious relations, we must be very cautious about simply equating all Vedic literature. Unpicking the resulting mess from these studies is laborious and time consuming. Almost as much as doing it from scratch. And if the scholarly literature is confused in this way, then we can see why the popular literature is confused. And given the importance of the gandharva to understanding the Buddhist afterlife, this is salutary.

To carry on with our survey of the Ṛgvedicgandharva, we may say that the relationship of the sun and the waters is a little counter-intuitive, but in at least some Vedic cosmogonic myth the first substance to emerge from the primordial chaos is water, and from water all things are created, including the sun. Soma is said to combine fire and water and thus bestow immortality (RV 4.18, 4.26; Doniger 1981: 128). It is worth noting the similarities with the so-called twin-miracle (yamaka-pātihāriya) in which the Buddha expresses fire and water from his body while hovering in the sky.

One of the important observations on the Vedic gandharva is that it lives (or they live) in the antarīkṣa or interim realm, the liminal space between earth (pṛthivī) and heaven (svarga). They are also associated with Soma in various ways. We saw that some stories attribute the theft of Soma to gandharvas, but they are also seen to empower Soma, eg RV 9.113.3

parjányavr̥ddham mahiṣáṃ

táṃ sū́ryasya duhitā́bharat

táṃ gandharvā́ḥ práty agr̥bhṇan

táṃ sóme rásam ā́dadhur

índrāyendo pári srava

The buffalo raised by Parjanya (God of rain),

It was brought by the daughter of Sūrya (the sun);

The gandharvas have received it,

Placed the juice in Soma.

O drop, flow for Indra.

The juice in Soma is squeezed out and consumed. It not only makes the sacrifice efficacious, but also produces the drug which releases the imagination and the tongue of the kavi or poet. However this only complicates the picture of the gandharva's relationship with Soma. Soma is of central important to the ritual cult of the Brahmins, and thus to positively associate a divine entity with Soma is certainly to give it a certain cachet or importance. The trouble is that while both myths allow gandharvas a facilitating role with respect to Soma, it is different in each case. Are they reflexes of a common myth or are they two distinct myths that happen to have been collected when the various Brahmin tribes combined their stories to form the Ṛgveda?

So far as I can tell there is only one Vedic sūkta, RV 10.177 (especially verse 2), which associates gandharva and the womb or garbha. Doniger links this sūkta with RV 10.123, which she describes as "strange and mystical" (190). The gandharvas reveal the secret name of the immortals (vidád gandharvó amŕ̥tāni nā́ma) and are carried up to heaven by their female partners the Apsaras. The story is partly about Indra (or an eagle) stealing Soma from the devas and thus is a further association of gandharva with Soma. The symbolism here is not at all obvious.

So far as I can tell there is only one Vedic sūkta, RV 10.177 (especially verse 2), which associates gandharva and the womb or garbha. Doniger links this sūkta with RV 10.123, which she describes as "strange and mystical" (190). The gandharvas reveal the secret name of the immortals (vidád gandharvó amŕ̥tāni nā́ma) and are carried up to heaven by their female partners the Apsaras. The story is partly about Indra (or an eagle) stealing Soma from the devas and thus is a further association of gandharva with Soma. The symbolism here is not at all obvious.

pataṃgó vā́cam mánasā bibharti

tā́ṃ gandharvó avadad gárbhe antáḥ

tā́ṃ dyótamānāṃ svaríyam manīṣā́m

r̥tásya padé kaváyo ní pānti || 10.177.2 ||

The bird carries speech in its mind,

The gandharva spoke that inside the womb;

That revelation shining like the sun,

The poets guard as a sign of cosmic order.

It's possible here that pataṃga 'bird' (literally 'goes by flying') refers to the gandharva, later as we'll see a Buddhist text refers to gandharvas as 'sky-goers' vihaṅgama. It's quite possible that birds were the inspiration for the gandharvas: little musical entities occupying and flying about in the sky. William K. Mahony (1998) interprets the bird as symbolising the sun on one level, the cosmic order (ṛta) on another, and also "the inner light of insight or visionary understanding residing with the poet's heart" (73; Cf. Wijesekere 78-80). The breadth of this reading also shows how the texts are wide open to interpretation. Some of this symbolism appears to be intended, but we always have the suspicion that the commentator sees what they wish to see because the references are vague enough to allow it.

There is really nothing in these Vedic stories that hints at a role for gandharvas in conception. Apart from the rather muddled way in which gandharvas appear (mirrored by their muddled treatment by scholars) we learn almost nothing that is relevant to our investigation of the role of the gandharva in conception or existence in the antarābhava.

In his article on the Pali gandhabba (= Skt gandharva) Anālayo (2008), citing a recent article by Thomas Oberlies, suggests that the Vedic gandharva"had the particular function of transmitting things from one world to another" and that it was a "god of transfer" (96). However, since the Buddhist gandhabba is a being to be born, rather than a god of conception, he concludes that the word gandhabba lost this connotation (96). Is Oberlies referring to the myth of stealing Soma? I cannot see any other example of gandharvas associated with transmission, but this can hardly be linked to conception. Oberlies's article is in German, so I cannot investigate the reasoning behind this claim, but I cannot see that the word gandharvaever had the connotation of "god of transfer". By contrast Cuevas says "gandharvas are not identified in the early Upaniṣads as transitional beings" (284).

We move now, perhaps 700 or 800 years forward in time from the composition of the Ṛgveda, depending on the dates assigned to the composition of our texts, to the (Pre-Buddhist) Early Upaniṣads. Here we are in an entirely different landscape. Brahmins lost the plant that produced the Soma drug and adopted a non-psycho-active substitute, the ritual became much more formalistic, and the focus of the Brahmanical religion had begun to shift from the cosmic harmony or ṛta, to the cosmic absolute or brahman. However various scholars have shown that Buddhist texts are cognizant of certain themes and ideas from this tradition, so it is a likely hunting ground for understanding.

Gandharva in the Early Upaniṣads

There is really nothing in these Vedic stories that hints at a role for gandharvas in conception. Apart from the rather muddled way in which gandharvas appear (mirrored by their muddled treatment by scholars) we learn almost nothing that is relevant to our investigation of the role of the gandharva in conception or existence in the antarābhava.

In his article on the Pali gandhabba (= Skt gandharva) Anālayo (2008), citing a recent article by Thomas Oberlies, suggests that the Vedic gandharva"had the particular function of transmitting things from one world to another" and that it was a "god of transfer" (96). However, since the Buddhist gandhabba is a being to be born, rather than a god of conception, he concludes that the word gandhabba lost this connotation (96). Is Oberlies referring to the myth of stealing Soma? I cannot see any other example of gandharvas associated with transmission, but this can hardly be linked to conception. Oberlies's article is in German, so I cannot investigate the reasoning behind this claim, but I cannot see that the word gandharvaever had the connotation of "god of transfer". By contrast Cuevas says "gandharvas are not identified in the early Upaniṣads as transitional beings" (284).

We move now, perhaps 700 or 800 years forward in time from the composition of the Ṛgveda, depending on the dates assigned to the composition of our texts, to the (Pre-Buddhist) Early Upaniṣads. Here we are in an entirely different landscape. Brahmins lost the plant that produced the Soma drug and adopted a non-psycho-active substitute, the ritual became much more formalistic, and the focus of the Brahmanical religion had begun to shift from the cosmic harmony or ṛta, to the cosmic absolute or brahman. However various scholars have shown that Buddhist texts are cognizant of certain themes and ideas from this tradition, so it is a likely hunting ground for understanding.

Gandharva in the Early Upaniṣads

Generally speaking in the Upaniṣads, gandharvas are a form of non-human beings who occupy a realm located between the ancestor-realm (pitṛloka) in the sky (antarīkṣa) and heaven (svarga) where the devas live. Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (BU 3.6.1) describes the dependencies of the various realms, listed in order. We find the intermediate region woven on the basis of the gandharva world (gandharvaloka). This is in turn woven on the basis of worlds of the sun, moon, stars and devas, etc, with the ultimate basis being the worlds of brahman (brahmalokā plural). BU 4.3.33 compares the bliss experienced by various types of beings in various realms, with more refined beings experiencing 100 times more bliss than less refined beings. The order here is manuṣya, the world won by the ancestors (pitṝṇāṃ jitaloka), realm of the gandharvas (gandharvaloka), the gods of rituals (karmadevā), gods of generation (ājānadevā), the realm of the progenitor (prajāpatiloka), the realm of Brahman (brahmanloka). A similar statement is found in the Taittirīya Upaniṣad (TU 2.8). In the Kaṭha Upaniṣad (KaU 6.5) one may gain a body on the basis of realising Brahman. In this world it is like a reflection in a mirror; in the ancestor realm it is like a dream; in the gandharva realm like an image in water; and in the world of brahman it is like shadow and light.

BU 3.3.1 describes a young woman possessed by a gandharva (gandharva-gṛhīta). Interesting the other protagonists learning the name of the gandharva ask him questions about the ends of the worlds (lokānāmantān). Contrast this with the possession we saw above at RV 10.85, which focuses on exorcising the gandharva. Similarly at BU 3.7.1 a man's wife is possessed by a gandharva who proceeds the question everyone present on the sacrifice (like a guru). In both cases the information gleaned from dialoguing with a gandharva is used to test Yājñavalkya, who of course always knows the answers to their questions.

Here the various associations of gandharvas found in the Ṛgveda are almost all lost. No sun, no Soma, no waters; not the father of Yama or any of that. Apart from the fact that gandharvas are beings who live in the sky, but are lower in the hierarchy than devas, there is nothing much here to inform our understanding of the gandharvas, and nothing at all that hints at a role in conception. Gandharvas remain in the background. However there is another body of myth and legend in the Epics, i.e. the Mahābhārata and Ramāyāna, and older Purāṇas where we often find themes and figures in common with Buddhist texts.

Other Vedic Literature

Here the various associations of gandharvas found in the Ṛgveda are almost all lost. No sun, no Soma, no waters; not the father of Yama or any of that. Apart from the fact that gandharvas are beings who live in the sky, but are lower in the hierarchy than devas, there is nothing much here to inform our understanding of the gandharvas, and nothing at all that hints at a role in conception. Gandharvas remain in the background. However there is another body of myth and legend in the Epics, i.e. the Mahābhārata and Ramāyāna, and older Purāṇas where we often find themes and figures in common with Buddhist texts.

Other Vedic Literature

Ideally we would survey the gandharva in the Epics and Purāṇas, though the scale of the literature is enormous and largely unfamiliar to me. The dates of composition are doubtful and most likely stretch over many centuries. In the Mahābhārata we find gandharvas portrayed as celestial musicians. Finally a substantial connection to Buddhist gandharvas! A gandharva named Citrasena teaches music and dance to Arjuna for example in book three (Vanaparva III, 44, 1793, 1795). However the gandharvas are also warriors who teach Arjuna the arts of war.

One of the themes in the modern comparative literature, Wijesekere dedicates several pages to this theme is the connection between gandharvas and centaurs. I have seen frequent casual references to kinnaras (or kiṃnara) as a sub-type of gandharva in the Mahābhārata, which seems to be a reference to MBh 2.10.14a "The gandharvas called kiṃnaras..." (किंनरा नाम गन्धर्वा) followed by a list of other 25 other names for gandharvas (translation here). On another occasion it might be interesting to compare this section of the Mahābhārata with the Āṭānāṭiya Sutta (DN 32) with which there seem to be superficial similarities. Equally there are frequent references to kinnaras as horse-headed, horse-faced (i.e. aśvamukha), or half-horse. Via Monier-Williams dictionary I located one reference to kiṃnaras as aśvamukha in a 7th Century work called Kādambarī (hardly relevant to early Buddhism). I'll return to this below.

We also find reference to gandharva-nagara'city of gandharvas' in the Mahābhārata and other texts where is it stands for an illusion. To be like a city of the gandharvas is to be like a dream for example, or a magic show. This simile is also common in Buddhist works (See e.g. the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism sv. gandharva-nagara)

When looking for the roots of the gandharva as it appears in Buddhist texts, the Epics and Purāṇas would seem to be more fruitful. We can tentatively say that the Vedas and Upaniṣads are the texts of religious specialists whereas the Epics have a more popular flavour. The former are full of metaphysical speculation; the latter focus on morality plays. The former are concerned with ultimate truths; the latter with cultural identity. These generalisations over-simplify the situation somewhat, but give a flavour of the main themes. The Indian Epics have much in common with the Greek Epics of Homer, with active gods, heroic humans and larger than life scale of actions; whereas the Ṛgveda might be likened to some of the Hebrew Psalms especially those which praise God.

That said I have not found any reference to a role in conception in any non-Buddhist text.

Gandharva as an Indo-European Phenomenon.

Wijesekere makes a great deal of the similarity of the Sanskrit gandharva and the Avestan gaṇdarǝba (variant spellings include gaṇdərəβa- or gaṇdaraβa-, where βa is an aspirated ba that we would usually write bha in Sanskrit; Wijesekere spells it gandharewa). Gaṇdarǝba was the name of a monster living in the lake Vourukaṧa. His epithet zairi-pāšna- meaning 'yellow-heeled' rather than "golden hooved" weakens Wijesekere's argument for links to centaurs.

Certainly the names are cognate. However, the stories about them seem unrelated and it's difficult to see any similarity beyond the name. This is also true when comparing gandharva in the Ṛgveda and the Upaniṣads, or any of these with the Buddhist gandharvas. Perhaps the name became a floating signifier for any kind of minor god? We do see this trend in other minor gods such as nāgas and yakṣas (See Sutherland 1991). For more on the possible connection, see Panaino (2012).

The suggested connection with the Greek Κένταυρος kéntauros (Latin centaurus) remains speculative. One argument for it was put forward by Georges Dumézil (1948: 29-30, 38), but like Wijesekere, Dumézil is rather too loose in his reasoning. He simply asserts, with no citation, that "in later writings the (masculine plural) Gandharva are beings with horses' heads and men's torsos who live in a special world of their own." (28). As we've seen above this connection seems to rest on a single reference to kinnaras as aśvamukha and another single reference to gandharvas called kinnara. By page 38 he has forgotten how flimsy this reasoning is and further boldly asserts that gandharvas are "half-horse"! Presumably in the magical world he is thinking of, being half-horse is no barrier to flying through the air or playing a musical instrument. Hopkins (1968) also favours some relationship between gandharva and centaur, but he also seems to be stretching his evidence beyond breaking point.

Even if there is some connection based on these tenuous links, they don't seem to tell us anything about the Buddhist gandharva and its role in the continuity of the person through saṃsāra.

Certainly the names are cognate. However, the stories about them seem unrelated and it's difficult to see any similarity beyond the name. This is also true when comparing gandharva in the Ṛgveda and the Upaniṣads, or any of these with the Buddhist gandharvas. Perhaps the name became a floating signifier for any kind of minor god? We do see this trend in other minor gods such as nāgas and yakṣas (See Sutherland 1991). For more on the possible connection, see Panaino (2012).

The suggested connection with the Greek Κένταυρος kéntauros (Latin centaurus) remains speculative. One argument for it was put forward by Georges Dumézil (1948: 29-30, 38), but like Wijesekere, Dumézil is rather too loose in his reasoning. He simply asserts, with no citation, that "in later writings the (masculine plural) Gandharva are beings with horses' heads and men's torsos who live in a special world of their own." (28). As we've seen above this connection seems to rest on a single reference to kinnaras as aśvamukha and another single reference to gandharvas called kinnara. By page 38 he has forgotten how flimsy this reasoning is and further boldly asserts that gandharvas are "half-horse"! Presumably in the magical world he is thinking of, being half-horse is no barrier to flying through the air or playing a musical instrument. Hopkins (1968) also favours some relationship between gandharva and centaur, but he also seems to be stretching his evidence beyond breaking point.

Even if there is some connection based on these tenuous links, they don't seem to tell us anything about the Buddhist gandharva and its role in the continuity of the person through saṃsāra.

Conclusions

In investigating gandharva we are struck by the almost ubiquitous confusion in the modern sources. This may be because the primary sources are limited in scope, vague in content, and from vastly different time periods. Far too little attention paid to the historical context of such mentions as we find. We simply cannot conflate early and late Vedic sources for example; nor Veda and Epic references. Adding all the vague references together does not clarify anything. What makes Wijesekere's account so difficult to read is that he makes no distinctions whatever between the stories: all are given equal weight. Where there is a disconnection or explanatory gap he fills it with a Romantic leap of imagination, weaving a narrative that owes as much to his own interpretation as it does to the text.

The methods used for dealing with the gandharvas in literature are misleading. Instead, I propose that we pay attention to the many centuries between versions of the stories and identify the gandharva as a bit player whose role is altered from time to time. The roles are distinct rather than cumulative. The thief of soma is not the celestial musician and so on. All that links these characters and characteristics is the name. Gandharva is a mythic widget. Note also the Iranian and Indian stories of gandharva seem to be completely unrelated. So the name might be Indo-Iranian, but the being is not. It is an error to treat the name as a rubric for all the many qualities associated with it over the centuries. When the name gandharva takes on new characteristics, it sheds the old. In the case of the gandharva, the many facets are not compatible. The early and late Vedic literature, the Epics and Purāṇas, even the Zoroastrian Avesta, certainly know the gandharva, but the various versions of these beings have little if anything in common with each other, let along Buddhist usage (as will be more clear next week as we survey Buddhist texts). Vedic gandharvas are very minor gods, with shifting associated symbolism.

I've complained before about the tendency in modern scholarship to seek singularities in our narratives of the past (see Unresolvable Plurality in Buddhist Metaphysics?) and proposed an alternative to the 'evolutionary tree' metaphor in the braided river (see Evolution: Trees and Braids). The attempt to simplify a complex picture by positing a single originating point, or an overarching rubric falsifies the record. One name obscures considerable narrative complexity for a being that is only mentioned a handful of times.

Where there is some apparent crossover with Buddhist gandharvas it is in the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas. The connection between Buddhist myth and the Mahābhārata has to date received far too little attention. Perhaps because the Mahābhārata is a massive corpus in its own right, the study of which is a specialist subject in its own right. However nothing in any of the sources surveyed sheds any light at all on the gandharva as interim being or its role in conception. This role seems to be entirely a Buddhist innovation.

BibliographyThe methods used for dealing with the gandharvas in literature are misleading. Instead, I propose that we pay attention to the many centuries between versions of the stories and identify the gandharva as a bit player whose role is altered from time to time. The roles are distinct rather than cumulative. The thief of soma is not the celestial musician and so on. All that links these characters and characteristics is the name. Gandharva is a mythic widget. Note also the Iranian and Indian stories of gandharva seem to be completely unrelated. So the name might be Indo-Iranian, but the being is not. It is an error to treat the name as a rubric for all the many qualities associated with it over the centuries. When the name gandharva takes on new characteristics, it sheds the old. In the case of the gandharva, the many facets are not compatible. The early and late Vedic literature, the Epics and Purāṇas, even the Zoroastrian Avesta, certainly know the gandharva, but the various versions of these beings have little if anything in common with each other, let along Buddhist usage (as will be more clear next week as we survey Buddhist texts). Vedic gandharvas are very minor gods, with shifting associated symbolism.

I've complained before about the tendency in modern scholarship to seek singularities in our narratives of the past (see Unresolvable Plurality in Buddhist Metaphysics?) and proposed an alternative to the 'evolutionary tree' metaphor in the braided river (see Evolution: Trees and Braids). The attempt to simplify a complex picture by positing a single originating point, or an overarching rubric falsifies the record. One name obscures considerable narrative complexity for a being that is only mentioned a handful of times.

Where there is some apparent crossover with Buddhist gandharvas it is in the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas. The connection between Buddhist myth and the Mahābhārata has to date received far too little attention. Perhaps because the Mahābhārata is a massive corpus in its own right, the study of which is a specialist subject in its own right. However nothing in any of the sources surveyed sheds any light at all on the gandharva as interim being or its role in conception. This role seems to be entirely a Buddhist innovation.

~~oOo~~

Anālayo. (2008) 'Rebirth and the gandhabba.'Journal of Buddhist Studies 1: 91-105. Republished by Anālayo with corrections of publishing errors: http://www.buddhismuskunde.uni-hamburg.de/fileadmin/pdf/analayo/RebirthGandhabba.pdf

Cuevas, Bryan Jaré. (1996). 'Predecessors and Prototypes: Towards a Conceptual History of the Buddhist Antarabhava.' Numen 43(3): 263-302.

Doniger, Wendy O'Flaherty. (1981) The Rig Veda: An Anthology. Penguin.

Dumézil, Georges. (1948) Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty. (Translated by Derek Coltman 1988). Zone Books. https://archive.org/details/Mitra-varunaAnEssayOnTwoIndo-europeanRepresentationsOfSovereignty

Eggeling, Julius. (1885), Satapatha Brahmana Part II (Sacred Books of the East; 26), at sacred-texts.com

Gombrich, Richard (2009). What the Buddha Thought. Equinox.

Hopkins, Edward Washburn. (1968) Epic Mythology. Biblo & Tannen.

Mahony, William K. (1998) The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. SUNY Press.

Panaino, Antonio. (2012) 'Gaṇdarǝba.'Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. X, Fasc. 3, pp. 267-269. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gandareba-

Pokorny, Julius (1959) Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Bern: Francke, 1989. Adapted online: http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/ielex/

Sutherland, Gail Hinich, (1991) The Disguises of the Demon: The Development of the Yaksa in Hinduism and Buddhism. SUNY press.

Wijesekere, O. H. De A. (1945) 'Vedic Gandharva and the Pali Gandhabba.'University of Ceylon Review. 3(1) April: 73-107.

Wilson, Horace Hayman (1840). The Vishnu Purana. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/vp/vp039.htm

Witzel, Michael (1999) 'Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rigvedic, Middle and Late Vedic).' Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 5(1). http://www.ejvs.laurasianacademy.com/ejvs0501/ejvs0501article.pdf