Reality is a slippery concept. I hesitate to even mention it. Science fiction author Philip K Dick said, "reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn't go away". Reality is that which has the quality of being real. However, "real" is only ever defined circularly. Real is actual, existent, true: each of these words defines the others. The word comes from Latin res, but this word has an uncertain origin. I'm going to try to avoid scare quotes, but in fact if any words deserves them all the time, then real and reality do.

This essay will look at reality by beginning with experiences that people would say are not real. This is also an awkward proposition. The unreal experience can seem to be real, can seem to be more real than real. Aren't we always in the position of the Zen master who could not tell if he was a man dreaming he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was a man? And what do I mean when I emphasise that an experience is real or unreal as opposed to saying that we have an experience of something that is real? Can we have real experiences of unreal objects? Or vice versa? With these questions in mind, let's begin with hallucinations!

Hallucinations.

What is an hallucination? At first, in the early 16th century, the word just referred to a wandering mind. Only in 1830 did French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Esquirol use it to refer to what until then might have been called "apparitions". An hallucination is, generally speaking, a perception arising in the absence of any external stimulus. But crucially what distinguishes an hallucination from a misperception or imagination is that we believe that the perception

does arise from an external stimulus. By this definition, hallucinations are difficult to distinguish from dreams. The world we interact with in dreams does seem external to us. However, except for a few strange circumstances, which we'll mention below, dreams only occur while we are

asleep. Hallucinations are waking experiences. It is of course possible to mistake one state for the other, but seldom for long. If one resists the "

Guru Effect", the Zen master sounds confused rather than profound.

Hallucinations occur across all the sensory modes of the human sensorium, though visual and auditory hallucinations are by far the most common. Very often hallucinations take on a human form. When we see things that are not there, we often see faces (see also the phenomenon called

pareidolia), or people; when we hear things we hear voices or music. Another common hallucination is to feel the presence of another person. Hallucinatory perceptions vary in their clarity and intensity. Some are merely vague feelings, such as an indefinable sense of dread before a migraine attack for example. Other hallucinations seem as real as reality, or in other words are indistinguishable from reality and there is nothing to alert us that we are not simply experiencing what is there. At other times hallucinations can be preternaturally vivid and hyper-real. We may see colours more vivid than any in reality, like a heavily saturated or "

high dynamic range" photograph; or we may see colours which seem not to have any real world analogue (and after all Newton invented the colour indigo when he named the colours of the rainbow). The level of similarity to reality has a huge influence on how we interpret hallucinations, but before going further into this topic, we need to say something about the circumstances under which we have hallucinations.

Because of taboos surrounding hallucinations they tend to be under reported. In the infamous

Rosenhan experiment several researchers presented themselves at psychiatric hospitals and said that they had heard a voice say to them "a resounding thud", but had not heard any voices since. They did not feign any other psychiatric symptoms. But all were diagnosed with a serious mental disorder, usually schizophrenia, prescribed antipsychotic medications and hospitalised for a period of some weeks. We fear being judged mad if we admit to perceiving things that aren't there, except under special circumstances that I will outline in due course.

Hallucinations may occur with sudden loss of sight or hearing. In Charles Bonnet Syndrome for example those who lose their sight hallucinate people that move around but do not interact with them. The hallucinations are compelling at first, but the sufferer usually realises quite quickly that they are not real. Phantom limb pain is an hallucination associated with loss of a limb and the felt sensations associated with it. Though some people born without limbs, due to birth defects, may also feel phantom limbs. Nor need the loss of sensory perception be organic. Spending time in a sensory deprivation chamber can also stimulate hallucinations. It is quite common to experience auditory hallucinations in anechoic chambers (spaces which do not reflect sound). Some types of meditation involve training the mind to withdraw attention from the senses and this may elicit the "visions" that some people have in concentrated states.

Many hallucinations are caused by an illness of some kind. People with Parkinson's Disease can have hallucinations associated with taking the medicine L-dopa. People who suffer from epilepsy can have a wide range of hallucinations. Migraine suffers regularly have distorted sense perception before the onset of headaches, and this very often involves so-called auras - lights in the visual field, often in characteristic zigzag patterns. Some however have more drastic symptoms. It is thought by some that Lewis Carroll suffered from migraine and some of the visionary aspects of his Alice in Wonderland stories are attributable to his hallucinations. People who have high fevers frequently hallucinate, as do those with extreme starvation or dehydration. The austerities pursued by various religious orders often involve extreme physical stress designed to bring on 'visions'. Other kinds of stress or shock can also result in hallucinations, from the intrusive memories of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder to the very commonly felt presence of a loved one after they die. One study of the latter suggested that 50% of people felt the physical presence of the deceased, sometimes for weeks after the death. Stressful situations, such as accidents or surgery, can cause the common hallucination of being outside one's body. The so-called out of body experience is quite well studied. Another common category of hallucinations is the near death experience. These are less well studied in the sense of the mechanisms involved, but many of the narrative interpretations have been collected and published.

The other most obvious source for hallucination is altered states. Many drugs produce hallucinations and there are instances of humans using hallucinogens throughout recorded history and evidence stretching back into pre-history. Excessive use of a drug like alcohol can produce hallucinations, when moderate doses do not. Similarly suddenly stopping some drugs after heavy use can cause hallucinations. However there are other ways to disrupt the brain. We've already mentioned fever for example. Nowadays magnetic or electrical stimulation have are used to disrupt brain functioning, sometimes producing hallucinations. Meditation is another way to get into an altered state, and as we've mentioned many people have hallucinations while meditating.

A major source of hallucinations is associated with sleep. These occur when dream states blend into waking states. Sleep related hallucinations may be hypnagogic or hypnopompic. The former occur in the transition from wakefulness to sleep, while the latter occur when going from sleep to wakefulness, though the distinction seems mostly semantic. One of the most common hypnopompic hallucinations is associated with sleep paralysis. While in a dream state the body is usually prevented from moving by a reflex - presumably it evolved to stop us falling out of trees when we dreamed. This is reflex is relaxed in sleep walking. In a classic sleep paralysis "nightmare" one wakes, but is unable to move or speak. And one feels the presence of someone or some thing. Very often because of being unable to move this feeling is accompanied by fear or even panic as the presence seem malevolent. Other kinds of dream type imagery can invade the waking state as well, especially with prolonged sleep deprivation.

Clearly there is a lot of scope for hallucinating and it seems likely that everyone experiences hallucinations at one time or another, without any suggestion of psychosis or mental ill-health. How we interpret these experiences seems to depend on a complex mix of factors including culture, religion, and the specific circumstances.

Interpreting Hallucinations.

Clearly from the medical perspective some hallucinations have valuable diagnostic value. If I have the visual disturbances typical of migraine then my doctor can make the appropriate diagnosis and recommend I avoid those foods known to trigger migraines and take specific medications either to prevent or mitigate them. Hallucinations make help to locate a brain tumour by their specific content - visual hallucinations might be caused by a tumour in the visual centre for example. Similarly for seizures. Persistently hearing voices may be a sign of psychosis (though many people who hear voices are not psychotic). And so on.

But the medical interpretation has its limitation both in applicability and attractiveness. For those who are not ill, the significance of their hallucination may range from a trivial annoyance, right up to a revelation from God. When hallucinations are particularly vivid or accompanied by feelings of bliss or well-being this might be more easily understood in religious terms. Hallucinations can be interpreted as windows onto another reality. The other reality may in fact seem more real than reality (hallucinations may appear hyper-real).

How we interpret an hallucination will depend to some extent on how we think our testimony will be received. If I tell a doctor I hallucinated voices, I will most likely be diagnosed with some psychopathology or physical illness. If I tell my Buddhist friends I had a vision of the Buddha, I'll be encouraged and perhaps celebrated (my Buddhist Teacher's visions are celebrated as evidence of his holiness by some of his disciples). On the other hand, the person who believes that God speaks to them or that they were abducted by aliens is frequently a figure of fun.

However, we run into problems when we interpret private experience as public reality. When we extrapolate from private experience to public ontology we almost inevitably go astray.

Towards Definitions of RealitiesWhat hallucinations and other misperceptions show is that definitions of reality that depend on individual perceptions are weak because an individual can easily be fooled into perceiving things are we would not consider real. This points to the need for definitions of reality that are based on commonality. Indeed there seem to be two approaches to defining reality.

The first approach we can call "consensus reality". The image accompanying this essay is of a small blue glass sphere I've owned for many years. Most people, unless they are trained to think differently, are naive Realists. If I was a naive Realist I would take the perception of my blue glass sphere on face value. I would take my experience for reality. This approximation turns out to be a workable rule of thumb. Reality must be not too different from how we perceive it to be, or we would be constantly banging into things, falling over and getting lost. And in fact most of the time we avoid obstacles, stay on our feet, and navigate to the supermarket and back home without much trouble. Clearly the match is not perfect because sometimes our perceptions do mislead us, but most of the time we do pretty well. I can toss my glass sphere from hand to hand quite easily and accurately (if I had three I could juggle them). For most people being a naive Realist is no great disadvantage. Now, when a bunch of naive Realists get together, because their maps of the world are pretty accurate, they can get a high degree of consensus about what the world is like, at least on a physical level. This is what I would call "consensus reality". It's real in the sense that it provides an accurate model for navigating the world. I'm not a believer in absolute reality in any case, but this consensus reality is contingent and relative.

Things get more complicated if we are talking about culture - economics and politics are quite difficult to get agreement on. Britons are about to have a general election. Clearly public opinion is deeply divided in Britain at the moment. The likelihood is that no one party will have a majority in the House of Commons. Thus arguments about policies take on an added verve. Should we continue to have austerity in preference to all other economic approaches? Does it ring true that the proponents of austerity are currently throwing out uncosted election bribes every day, all of which contradict their so-called long term economic plan? Is Labour a credible alternative for those who want to remove the Tories from power? Does the fact that the former left-wing party now espouses Neoliberal economic policy put off traditional voters, or has everyone bought the Neoliberal propaganda? Given that no party will have a majority, what shape will the government take? Generally speaking once humans are involved then things get messy. Reality in this sense is more difficult to define.

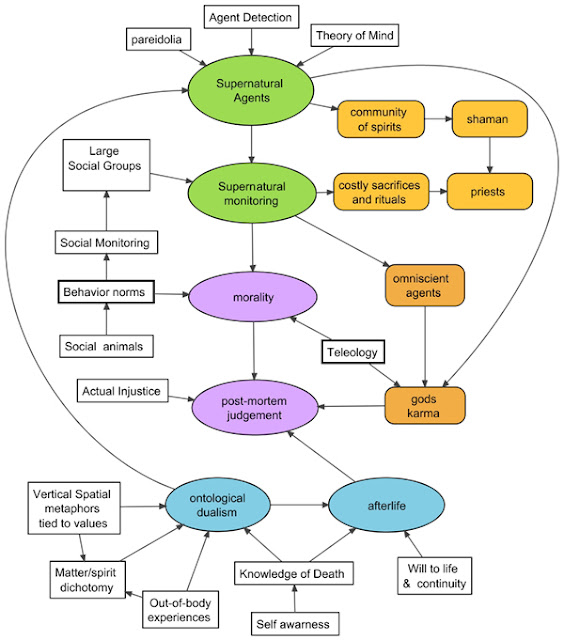

A feature of consensus reality is that it can be parasitised by beliefs that are based on psychological imperatives. For example almost all humans believe in life after death, not because they see regularly see people coming back to life, but because it seems preferable to the alternative (on the basis of this belief, some people have gone looking for evidence, but they set the evidentiary bar pretty low and suffer from strong confirmation bias). That said, belief in an afterlife is not trivial. People kill and die for their version of the afterlife; they create oppressive living conditions for themselves and others to try to ensure a good afterlife. The necessity of suffering in life is something that falls out of the metaphors we use to define the matter/spirit dichotomy (see

Metaphors and Materialism).

The contingency of consensus reality is what makes it unsatisfactory, especially in an age where empiricism has lent clarity and accuracy to other domains.

The second approach I'll call "empirical reality". If we come back to the blue glass sphere I own, and we apply scepticism and close observation we can come to somewhat different conclusions to naive Realism. Close observation for example shows that the light source and spatial relationship with the object affect how we see it. In the photo the sphere is lit from behind by an LED torch against white background. The dynamics of the camera lens and sensor, not to mention the Instagram processing, also affect how the picture comes out. We start to realise that the way the sphere looks is partly due to physical properties that are not obvious. For example, careful experimentation would show that because the glass has a high lead content (it is heavy for it's size) gives it a high refractive index compared to other transparent objects and this gives it a distinctive appearance. We might also discover that doping the glass with a small amount of some salt of copper or cobalt gives it that deep blue colour. We might discover the though it feels smooth the surface is minutely textured. And so on.

One of the most important features of this approach is that it relies on confirmation. An empiricist looks for repeatability before announcing their discovery. And it is only accepted by the wider community once it has been confirmed by other empiricists. This is why the announcing of one-off results to the news media is so irksome to serious scientists - it undermines the process and since one-offs often turn out to be anomalies, it casts unnecessary doubt on empiricism as a method. Careful empiricism is the most successful knowledge generating activity we've ever known. It has transformed our understanding of the world and our place in it, though often with unforeseen consequences. Empirical reality is also less liable to parasitisation by beliefs. Empiricism has antibodies for false beliefs. False beliefs do sometimes take hold, but the practitioners of empiricism are motivated in various ways to disprove current beliefs and so false beliefs get rooted out eventually.

What empiricism shows us is that although consensus reality is OK to be getting on with, there is a deeper reality, or perhaps that a deeper understanding of reality is possible. And over some centuries what we discover is that reality seems to have many such layers. Naive Realism is accurate enough on the human scale. But at the nano level we can talk about atoms and molecules to give a much more accurate picture. Atomic theory allows us to manipulate materials and invent new ones with great precision. On the appropriate scale atoms are real, it's just that on much smaller scales or at energy levels sufficient to break the atom into its constituent parts we find that a more accurate description involves sub-atomic particles. At a deeper level these particles are made up from quarks. And beyond that we think in terms of fields, which may well be the smallest scale reality in our universe. Going in the other direct we find that we can describe the universe pretty well until we start dealing with very large masses or very high velocities, then we must use relativistic descriptions to predict how matter will behave.

Compared to consensus reality we may call these deeper realities, "empirical realities". The plural must apply because at the appropriate scales of mass, energy and length, for all intents and purposes they are real. For example one could never observe a quark in a kilogram of matter, taking up 1000cm3 of space, at 20°C. Quarks don't really exist as separate entities under these conditions. To get any evidence of quarks at all we have to change these conditions by many orders of magnitude, i.e. to smash single protons together at close to the speed of light and observe the decay products. It may be that the Standard Model of physics is accurate enough for most purposes, but we know that it cannot hold at time = 0 in the universe because it implies infinities that are impossible. Those infinities tell us that something else is going on at the moment of the Big Bang, something we have yet to understand, though there are several plausible conjectures being explored at present.

All Together Now.So is there are ultimate reality? It may be that there is, but as far as I know we've not found it yet, nor any evidence for it. Reality depends to some extent who is looking, what they are looking for, and how they look. The idea that there is one reality and that all else is unreal is a dichotomy driven by theological legacies that I would trace back to monotheism. Monotheism creates all or nothing situations. Either you believe in the one god or you don't. Traditionally you are either for god or against; destined for heaven or for hell. It's a hermeneutic that pervades the minds of those whose cultures are now, or were until recently, in the grip of monotheistic religions.

So is my blue glass sphere real? If I threw it at your head you would certainly know it. It's dense and heavy enough that it would probably injure you. Thrown hard it might well kill you. That suggests a certain level of reality. Several times I've sat it on a table and asked a group to describe it. I've found that they all agree that it has certain physical qualities (spherical, blue, cool to touch etc). If it wasn't real at some level, then how would a group of people agree on it's description? If the qualities were not intrinsic to the object then how could multiple sensing subjects perceive the same qualities? If the object itself was not coordinating the shared perception by having intrinsic properties, we'd have to invent some other entity or force to explain the coincidence of perceptions. And that other coordinator would never be as simple or plausible as a real object.

Common or shared perceptions are typically left out of arguments about reality, especially by Buddhists. Buddhists will go to extraordinary lengths to assert that everything is connected, but then argue about perception as though there is only one person in the world. This is similar to the simplifying assumptions that macro-economists make so that they can use micro-economic concepts like supply and demand. Macro-models of supply and demand literally make the assumption that there is only one consumer and one product, selling for one price. In any other field, except Buddhism or economics, a requirement for an assumption as gross as this to validate the model, would contrarily be seen as falsifying the model. But all of Buddhist psychology argues as though there is a single mind, having sensory experiences one at a time, without reference to other minds.

In the Yogācāra context we often get the example of disciples arguing over where the flag moves or the wind moves. In thinking about this we must remember that in India "wind" (vāyu) is the principle underlying all movement. The master tells the disciples, "it is your mind that moves". Which on face value sounds profound, but points to a form of unhelpful Idealism that often ties unwary Buddhists in metaphysical knots. In terms of how to do meditation this is fine. But Buddhists often take it to be statement of ontological truth. The more interesting observation, for my money, is that all the disciplines and the master are agreed that there was a flag. This simple fact is something Idealism struggles to explain. If it was the minds of disciples that were moving, then what was it made them all see a moving flag at the same time? If it was not the flag itself, then what was it?

Of course perception is something that happens in our brains. In reality we do not see a blue sphere or a waving flag. What happens is that streams of photons are refracted, reflected, selectively transmitted and absorbed, and arrive in the retina where they are absorbed by light-sensitive cells that send electro-chemical signals to the visual centres of the brain, where a process we don't presently understand interprets the signals as shapes and colours in the world.

By comparing notes on the same object we get information about our sensory apparatus. And by comparing notes on different objects perceived by the same subjects, we get information about objects. Empiricism from multiple points of view produces knowledge about the world that is independent of observers as well as knowledge about how the observers produce knowledge.

However, while we can gain knowledge of the world, we have to question whether reality, in the sense of ultimate reality, is even a useful concept. We can certainly argue that atoms are more fundamental than macro-scale objects and quarks are more fundamental than atoms and fields more fundamental than quarks. But so what? We cannot normally perceive other scales and what happens on those scales does not affect our day to day decision making. Quantum mechanics is frequently invoked in this context, but quantum effects can only be observed in extremely unnatural circumstances. I can get to the supermarket and buy a loaf of bread without ever consciously invoking QM. It is true that computers have now automated the supermarket side of things, but it all worked before computers.

In Practice

Buddhists are often quick to point out that this kind of discussion about reality has no impact on practice. I think this is short sighted. Clarifying some of these details is vital for practice. Because at the very least it helps to clarify the object of our meditation. For example many Buddhists seem to believe that through meditation they will gain insight into ultimate reality. But thinking about reality makes this seem very unlikely. Ultimate reality is clearly not going to be understood through an individual's experience, since our ability to know anything is strictly limited. In order to have knowledge of reality as posited by Buddhists we would need a reality detecting faculty which is neither the five physical senses nor the mind. No such faculty is ever postulated by Buddhists. Nor is it conceivable. When we go back to the early Buddhist texts, they seem to agree that reality is nothing to do with the Buddhist goal. Buddhists look at and gain insight into experience rather than reality. Thus there is no need to postulate a special sense faculty required for knowledge conducive to liberation.

This distinction is important in focussing the mind of the meditator. If we are examining experience then that it a relatively straight-forward task, we have methods for doing so, and the process can be undertaken systematically and deliberately. However if what we are looking for is insight into the nature of reality then this cannot be undertaken systematically. Somehow reality will make itself known to us, we just have to rely on a kind of grace (I'm paraphrasing narratives I've heard my colleagues and others use). Seeking reality through meditation is a very different activity from seeking to understand experience. In fact as a passive process it can hardly be called an "activity" at all. Some schools of Buddhism completely excise the possibility of awakening-directed activity. One can only rely on external agents and forces in some forms of Pure Land Buddhism for example.

A classic example of the difference is to be found in my forthcoming article in the Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies (due out in May 2015) on the first sentence of the Heart Sutra. Conze, the "modern gnostic" as he styles himself, has Avalokiteśvara floating above the world engaged in mystical practices that by mystical powers afford him insight into the reality of the skandhas. In fact, and the Chinese and Tibetan versions bear this out, what Avalokiteśvara is doing in the Sanskrit manuscripts, is examining his experience using a skandha reflection and he sees that experience is not reality at all, that experience is contingent on reality and the mind overlapping. There is of course nothing new in this observation since it pervades early Buddhist texts as well.

The trouble with the mystical approach is that it removes Buddhism from the human sphere. Only a few individuals will ever be blessed by insight. The rest just have to take it on faith. On the other hand, if insight arises from the deliberate and systematic examination of experience, then this is literally open to everyone. When we invoke the concept of the "nature of reality" in the Buddhism we cut most people off from the goal of liberation. And we confuse many people about what the practices are and do. So in my view this is a discussion we urgently need to have.

One thing one often hears, especially from Baby Boomers who had access to LSD in the 1960s and 1970s (when tabs were

much stronger!) is that their experience of tripping opened doors to another reality, or affected how they viewed reality. The psychedelic experience can certainly be a compelling one. But let us think for a minute what is happening. LSD is thought to interact and interfere with brain systems that use the neurotransmitter serotonin (migraine also does this). It's not that suddenly a new reality external to the mind comes into existence or that we gain access to it. This is at best a metaphor. Changes in the way the brain processes information alter the way users

experience of the world. The fact that the changes feel profound is simply one of the changes. If we interpret an experience as being "profound" then the

profundity is simply another aspect of experience. The sense of profundity may be ascribed an intrinsic value over and above the experience which accompanied it. But we know that a sense of profundity can be switched on and off. People with depression, another phenomenon associated with serotonin, often have the sense that nothing has meaning, that nothing is beautiful. That everything is the opposite of profound. So too with bliss and all the other aspects of religious or mystical experiences. The mystic is not in touch with, not in, another reality. They simply interpret experience differently and it is peculiar to them (and thus fits the definition of an hallucination). In fact Aldous Huxley was right to refer to the "doors of perception" which is one way the Buddhist texts refer to the senses (i.e.

indriya-dvara).

Once I was talking to a Buddhist teacher about his experience of the breakdown of subject/object duality. For him this was a more profound experience than insight into the contingency of self. I pointed out our perceptual situation, that I was sitting facing the door and that he had his back to it. He had to admit that even with no sense of subject/object that his point of view was unchanged - he could not see the door without turning his head. Thus we have to take the "breakdown of subject/object duality" as a metaphor. It's tempting to say that his experience is subjective, but in Buddhist terms all experience is by definition both subjective and objective.

Metzinger's model of the first-person perspective has three target properties:

- mineness - a sense of ownership, particularly over the body.

- selfhood - the sense that "I am someone", and continuity through time.

- centredness - the sense that "I am the centre of my own subjective self".

As Metzinger's own work shows it is possible to interrupt these target properties and thus disrupt the first-person perspective. Meditation can do this too. But the resulting experience is not more real. It sounds as though it can be more

satisfying, though of course sometimes the disruption of the first person perspective can be devastating and debilitating. In part the narratives about reality in this context are attempts to valorise experiences. By referring to religious experiences as more real, we raise the value of the experience and the charisma of the person who experienced it. In other words this kind of discourse about reality is highly motivated.

Reality is Over-rated.Many religieux, especially Buddhists, seem excited by the idea that science proves their religious beliefs. Though this is usually accompanied by an excited rejection of science that disproves religious beliefs. Quantum Mechanics is invoked all too frequently - I've dealt with this fallacy on two occasions:

Buddhism and the Observer Effect in Quantum Mechanics (2014) and

Erwin Schrödinger Didn't Have a Cat. It reinforces the idea that religieux are only interested in proving what they believe, and not in truth per se. Religieux believe they know the truth already and simply want confirmation that they are so knowledgeable. Even if we exclude the blatantly mystical and fantastic from Buddhism, which many Western Buddhists do as a matter of course, we still find our beliefs challenged by science and even more so by history. But in fact Buddhists have no special insights into reality, let alone the nature of reality. Most of what Buddhists believe runs counter to the best explanations we have of reality. However this seems to me to be because we take insights about personal experience and try to use them as ontological theories. Buddhists are pretty good on the subject of experience. Buddhist practices are still useful for exploring experience. Used judiciously Buddhist theories are useful for understanding experience. Reality is not at all as Buddhists describe it, except that it is changeable, but then as I've said elsewhere:

Everything changes, but so what?

So it seems to me that "reality" is a concept with limited value. To some extent we do need to discuss what we can agree on and what we cannot. To some extent deeper concepts of reality enable engineers and scientists to work more efficiently. I don't need a very sophisticated concept of reality to jump on my bike and head down to the shop to buy a loaf of bread. Arguing about the inflated price of housing in the UK might take a more sophisticated version of reality, although this discussion is highly polarised because of the influence of ideologies. Making a modern computer requires a very precisely specified reality. But when it comes to religion, our ideas about reality become inflated and speculative. As far as Buddhism goes, speculation about reality seems to be a distraction, a hindrance. If we are to encourage everyone to explore their experience, which seems a laudable goal, then we need to reframe our narratives of what Buddhism is about and how it works to reflect this.

~~oOo~~

Further reading:

'The brain treats real and imaginary objects in the same way'. Science Blog. 6 Mar 2015.

Sacks, Oliver. (2012) Hallucinations. Picador.

Cima, Rosie. 'How Culture Affects Hallucinations'. Priceonomics.com. 22 Apr 2015.